The House leadership fumbled Duterte’s impeachment

Had Speaker Martin Romualdez allowed the first three impeachment complaints against Vice President Sara Duterte to work its way through the House Committee on Justice, he would probably not have suffered an embarrassing loss at the Supreme Court today.

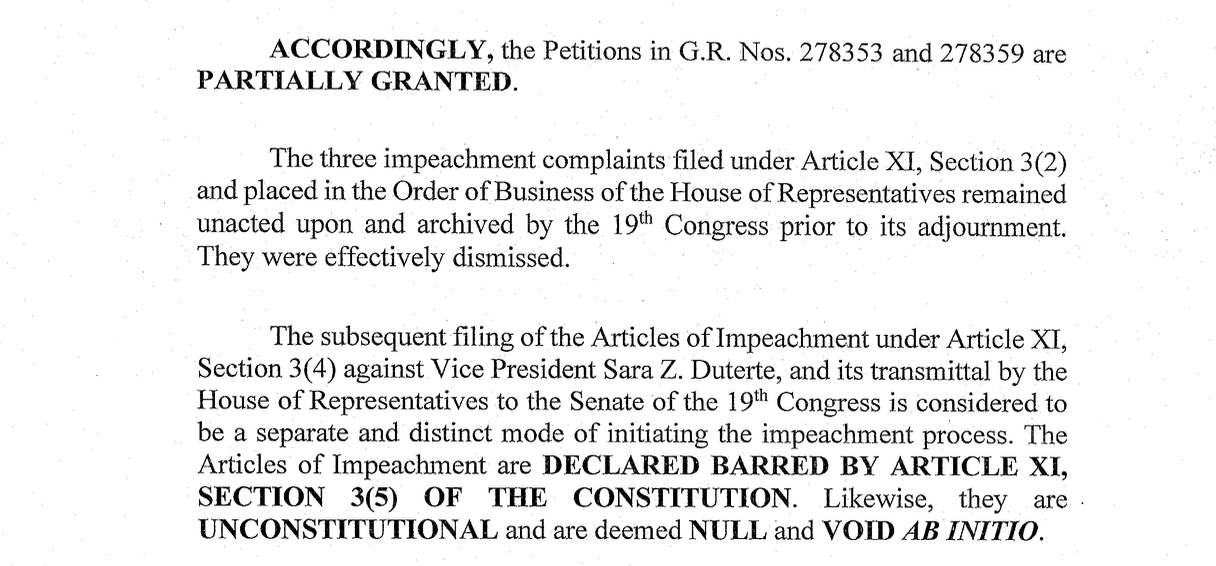

After all, today’s decision in Duterte v. House of Representatives only declared as unconstitutional the fourth impeachment complaint–the one crafted behind closed doors by the House leadership and endorsed by hundreds of lawmakers. Ostensibly, the first three impeachment complaints filed by minority lawmakers are not unconstitutional.

Sure, the House attained its purpose–to indict the vice-president. Politically, it was an attempt by the administration allies to shave off Duterte’s political capital heading to the 2025 midterm elections. But the unnecessary haste by the speaker–because partisan points had to be scored before exacting accountability–made the complaint legally infirm.

While the Supreme Court’s decision is a pyrrhic victory for Duterte (because the court, notably, clarified that they weren’t exonerating her), it is still a victory. Just last year, the vice-president was already fighting off several controversies over her misuse of public funds. But today, the Supreme Court handed her a partial vindication–immunity from a politically fraught impeachment process until February 2026. She can now hope that the next six months will be enough to cajole lawmakers into her fold, staving off further attempts to remove her from office.

But the consequences of the court’s decision does not end there. The unconstitutionality of the Marcos-Romualdez-led impeachment complaint also infected the genuine impeachment complaints filed by minority lawmakers, principally from AKBAYAN and the Makabayan Bloc.

Because Romualdez wanted a short-cut, his leadership decided to ignore the complaints filed by the progressive lawmakers. Hence, when the 19th Congress adjourned, the first three complaints were considered “terminated or dismissed.” The court said this is the point where the one-year ban applied. Simply put, the moment that the House didn’t act on the first three impeachment complaints, the ban came into effect.

As early as December 2024, progressive lawmakers were already calling out Romualdez for his failure to act on their complaints. Had the speaker allowed the complaints to move through the House, all parties would’ve had a chance to ventilate their positions. The lawmakers pushing for Duterte’s impeachment would’ve been able to make their case to the country–publicly (and not by mere signatures)–and each lawmaker would’ve had a chance to explain their position on the record. It would’ve been a great exercise of due process and fairness, and a chance for our institutions of government to show how our accountability mechanisms work.

But, as it turns out, the House leadership was also crafting one discreetly–not motivated by accountability, but by raw politics. In the end, their hurried indictment was declared illegal.

Jurisprudentially, the Supreme Court is not saying that the impeachment shortcut (the one-third endorsement that the House did) should no longer be done. Rather, the court was saying that the rudimentary rules of due process must still be observed when the fast-track method is being used. What the House leadership did–crafting articles of impeachment secretly and passing out a signature sheet among lawmakers–cannot be tolerated.

Fr. Joaquin G. Bernas S.J., a member of the 1986 constitutional commission, was already dubious of this fast-track method. He even called for its abolition! In an opinion piece published in TODAY on November 16, 2003, he wrote:

To my mind, this provision that bypasses deliberation by both committee and plenary is unwise. First, it denies the object of the complaint the opportunity to be heard, and second, it is an open temptation to sign under pressure and without deliberation. If ever we amend the Constitution, I believe that this is one of the provisions that should go.

The Filipino people require accountability from its public officers. We demand accountability from the vice-president over her questionable use of confidential and intelligence funds. We demand accountability from President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and his allies in Congress, particularly the speaker, for failing to heed the people’s demands for a clean and honest government.

Today, our political institutions have failed us. They have failed not because they decided to keep a corrupt vice-president in office. Rather, they failed to meaningfully act on the people’s demands for accountability. There’s no reason for avoiding a politically painful process when it is what the constitution requires of our leaders, because the people deserve no less.